Here is a link to my completed PhD thesis, which I finished in March 2015. I hope you enjoy it!

The end of the beginning

I’m currently writing up my thesis, with only a couple of weeks left to go. Hence the rather long silence on this blog, and the choice to stop updating from this point. I was intending to end this blog with a television interview that I conducted a couple of weeks back, but so far it seems like the interview has not made it to transmission – I’m assuming that my responses to their questions about selfies and psychological disorders weren’t quite what they were looking for (i.e. sensationalist and inflammatory), and they’ve chosen not to show it.

There’s still so much work to be done concerning selfies and women’s photography more generally, that I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of what I wanted to do. Still, as people keep telling me, a PhD is not your life’s work, and there’s plenty of time for all those other interesting topics and avenues of investigation. And so I end here, ready to begin again next month at my new job, a new project, and a new blog.

Many thanks for reading.

The ‘Picturing the Social’ Conference, November 2014

As I mentioned in my last post, I will be joining the University of Sheffield’s Picturing the Social project in January, which forms part of the Visual Social Media Lab. The project launched with a conference last week, and I was fortunate to be able to present a summary of my research so far, fitting a whole thesis into just under 20 minutes (which is an excellent way of focusing the mind on what you really want to say).

There have been some excellent write-ups of the conference, from Karen Patel and The Useful in Parts blog.

What I just wanted to note here was the sheer breadth of material that was covered – looking at images on social media might well seem like quite a niche topic, but this conference proved that this subject is anything but niche. We heard about Lin Prøitz’s work with young people, technology and futuristic visions of mobile telephones. Shawn Walker discussed link rot, and told us that unicorns can both code and conduct theoretical analyses. Rhys Crilley talked about the rather chilling topic of the British Army’s ‘clean’ version of war on Facebook, where pictures of dogs and tanks abound, but local Afghan people are conspicuously absent. And Gillian Rose introduced me to the concept of ‘visualisations’ – 3D renderings of non-existent spaces, which I had only noticed in the past because they seemed so uncanny.

These are only a few of the people who spoke, but I just wanted to give an indication of the range of topics we looked at – from war to links, and from visualisations to young people and technology. This is a really diverse and exciting field to be working in, and the Picturing the Social project is clearly going to be fascinating to work on. I can’t wait to get started!

Selfies and security

I’m talking at a conference this Friday in Sheffield, called ‘Picturing the Social’. It’s connected with the ESRC project of the same name that is happening as part of the Visual Social Media Lab at the University of Sheffield, and I’m lucky to be joining them in January as a research assistant.

In advance of the conference, a journalism student contacted me to ask me some questions. As I answered ‘why do people take selfies?’ with an annoying vague response – tl;dr version: ‘for lots of reasons’ – I thought of one possible motivation for taking selfies that hadn’t occurred to me until then: selfies are safe.

I had previously considered the post-9/11 effect on social media as being a question of authenticity, in which people are encouraged to not just be visibly present and knowable online, but also to be truthful. This discourse of authenticity has now reached its zenith, in that the NSA/MI5 surveillance of social media is predicated on the assumption that the information provided there is reliable. Additionally, Mark Zuckerberg’s insistence that ‘you have one identity’ also supports this drive towards authenticity, but only so that he can provide advertisers with ‘real people’ who can be approached as predictable and therefore malleable.

But what if this rise in security and anxiety had a different knock-on effect on social media? What if it made people look at themselves because they are the most inoffensive and unproblematic subject they can think of? In a climate where photography has been problematised and pushed out of so many spaces – from malls and airports to railway stations and schools – is a selfie the safest photograph you can take?

The Met Police’s website states:

“We encourage officers and the public to be vigilant against terrorism but recognise the importance not only of protecting the public from terrorism but also promoting the freedom of the public and the media to take and publish photographs.”

Photography and terrorism are here connected in a way that suggests that the former may legitimately be interpreted as a technique of the latter. Photography has a long history of being problematised in a way that is unlike any other form of artistic practice: it is seen as too easy, too automated, and in this case, it is too dangerous. When complains are made (such as by Vilém Flusser in Towards a Philosophy of Photography) about the repetitive nature of amateur photography, in which similar photographs are taken again and again, perhaps the law needs to be taken into account? Are repetitive photographs perhaps to be regarded as safe because lots of people are taking them? The threat of being punished for taking photographs of the wrong things cannot be discounted, and whereas photographing other people, buildings, cars etc. might get you into trouble, a photograph of one’s face contravenes no regulation: except the social injunction against vanity. And therein lies the problem – in seeking to avoid one form of social condemnation, selfie-takers are then vulnerable to another type of criticism…

Policing the Selfie

I’m surprised I haven’t seen selfie disipline like this before. In a You Tube video by Jena Kingsley, the presenter plays a prank on visitors to Central Park by dressing up as a cop and telling people not to take selfies. A surprising number comply, as if such an order could in any way be rational.

Kingsley starts her video by emoting to camera about the evils of selfies, and the need for someone to step in to stop the madness. Behind her, a sign declares that this is a ‘selfie-free zone’ from 7am to midnight, and that violators are ‘subject to $50 fine’.

The details are something we are familiar with – directives with time limits and penalties – which goes some of the way to explaining why this prank is possible. Forms of micro-discipline guide our behaviour every day, from no-smoking areas and grass that cannot be walked on, to the no-touching or no-photography rules in art galleries. So we are used to being told what, when, where and how we can do things. But these directives have a limit, and mostly relate to one’s harmonious participation in social spaces. So I would also argue that this stunt relies upon the cultural messages regarding selfies, which problematise the practice as something socially objectionable and worthy of condemnation. As a result of the kind of texts I have been examining on this blog, people’s enjoyment of taking selfies is always tempered with the understanding that they are some way illicit, leaving a space in which ‘no selfie zones’ could possibly be feasible.

Consider the reaction were Kingsley to have started forbidding people to wear hats, or drink water. The looks of confusion that people give her here would soon turn into outright anger, and she would very quickly be revealed to be just someone dressing up issuing strange and arbitrary orders.

She only lasts as long as she does precisely because her target is selfies. And only selfies – plenty of people are shown to be snapping away in the background whilst she is explaining to someone how problematic selfies are – using some flimsy rationale concerning young women’s self-esteem. Is the answer to young women’s low self-esteem to bring in more regulation concerning their behaviours? Her argument makes no sense, but then I assume it is not meant to.

At one point, Kingsley asks that people delete their selfies whilst she watches. A few are shown to comply, albeit grudgingly. In the last 15 years, photography has increasingly been problematised in a way that regards it as a potential security threat. One only needs to start taking pictures in a shopping centre or in airport security to see how vigorously ‘no photography’ rules are enforced. But here we see how this regulation has become normalised as a (potential) force enacting upon every type of photography. This is not a question of national security, but rather of enforcing social rules regarding conduct in public spaces – but yet both, at least as far as this prank goes, involve the use of the law to restrict photography.

Several people are shown to take selfies with Kingsley in the background, an act that demonstrates their understanding of the regulation she espouses as being ridiculous, as well as using selfies as a means to undermine her assumed authority. The young man’s act of selfie-taking, below, is therefore both a confirmation of Kingsley’s understanding of selfies as mischievous and uncontrollable, and an act of resistance to that interpretation.

Towards the end of the video, Kingsley offers to take photographs of several of her victims, reaffirming that some types of photograph are acceptable in contrast to the selfie. I would love to hear her explanation for this – for why it is so objectionable for a couple to photograph themselves, but yet it is fine for her to take a picture of them? It is at points like this that the ‘logic’ of selfie-taking as devalued starts to break down, and it becomes most apparent that these rules and assessments are purely arbitrary.

At the end of the video, Kingsley is confronted by a member of the park security and told to leave the area. After all, in his eyes, she is a nuisance to visitors; marching around micro-managing people’s leisure time whilst dressed as a cop (in itself a problematic and possibly illegal behaviour, I would have thought). By asking her to leave, the park guard is not just reasserting the park’s status as a space for personal relaxation, but also confirming that the social rules that ensure every visitor’s safety and enjoyment do not include anything regarding selfies.

The arm outstretched in a gesture of dismissal is therefore a means for protecting the right to similarly reach out one’s arm and take a selfie.

Blaming Selfies When Things Go Wrong

I was reading an article on the site Psychology Today, that was a response to the show Selfie (see my article on Selfie here. I would have written a follow-up on the series as a whole, but after watching the first episode, I don’t believe I could put myself through any more of that. It was quite spectacularly objectionable).

The Psychology Today article aimed to present quite a balanced view of selfie-taking, explaining the practice as something that exemplified the importance of social relations and esteem to our wellbeing. It seeks to mitigate the negative effects of selfie discourse by challenging the generalisations and gender bias, importantly highlighting the contradiction in the demands on young women, to be seen as attractive and yet not to be perceived as ‘vain’. But the article is problematic in that it explains the importance of society in forming and experiencing identities, and then asks whether it is a ‘good thing’ that selfies have become part of this – this seems like a loaded question. Surely social motivation can neither be universally good nor bad, but entirely dependent on context, outcome etc. And why does the incorporation of photography into a pre-existing social process pose such an enormous threat? The piece concludes by reinstating a problematic and excessive view of selfies and social media use more generally, as something that needs to be modified and controlled. To understand how specific this kind of discourse is, consider the number of articles that problematise books, music videos or films in this way, as something to be limited and as a target for continual outrage and concern. But then they do not constitute unruly entries into the public sphere, in that way that selfies do, and it is that participation, rather than what they ‘do’ for selfie-takers, that is the real ‘problem’.

But the real surprise was yet to come. There was only one comment underneath the article. I had to click on it to read it, and I was amazed:

Joan Rivers got killed during a simple proceedure because her “vain” Dr. took a “selfie.”

When it was suggested in the press that Rivers’ personal ENT doctor, Dr Gwen Korovin, took a selfie with her unconscious patient, there was outrage. Underneath one article, a commenter suggested:

What a complete breach of trust and professionalism. This doctor should lose his medical license permanently, in the very least, and possibly even face criminal charges for the selfie alone. Can doctors no longer be trusted with their unconscious patients?

This outrage entirely eclipsed the accompanying suggestion that alongside taking a photo, the doctor concerned had also performed an unathorised biopsy on Rivers. Taking photographs in this context would indeed be deeply unprofessional, but moreso than conducting procedures which the patient had not agreed to? Both accusations – of selfie and of biopsy – were heavily denied, as the product of hearsay at the clinic. The New York medical examiner ruled that Rivers died from oxygen starvation after she stopped breathing. It was reported that negligence was not found to be a contributing cause in her death, and that there was no biopsy. But this comment demonstrates the degree to which selfie-taking has been catastrophised within popular discourse – here, it is the selfie that killed Rivers. Not the use of anaesthetic at her age (81), not the fact that she wasn’t in a hospital and that treatment for her cardiac arrest was, as a result, delayed. It was the selfie – the quintessentially abject example of human depravity – that was to blame, for the popular understanding of selfies is that they do not have merely the capacity to annoy or engrage, they can also be lethal. Never mind any other contributing factors – it was the selfie. I only wish we could have heard what Rivers’ witty and acerbic reaction to this would have been.

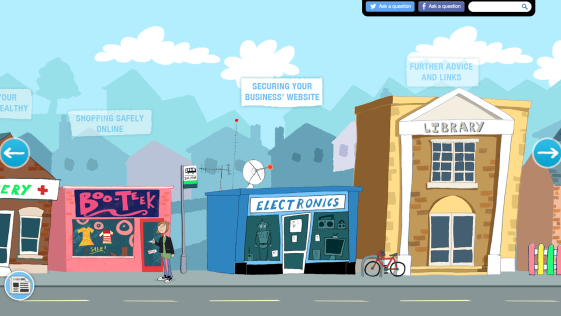

Safety and Self-Responsibility: The Game!

I have just been looking at the website Cyber Streetwise. The site describes itself as:

“a cross-government campaign, funded by the National Cyber Security Programme, and delivered in partnership with the private and voluntary sectors. The campaign is led by the Home Office, working closely with the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and the Cabinet Office.”

So what does this UK government initiative say about privacy and social media? It says:

It struck me that this government-sanctioned advice concerning social media was in fact consolidating the problem. Because the statement “never upload or say anything in social media that you don’t want the world to know” conceives of privacy as binary: you are either private with your thoughts, or you are sharing them with everyone. And this dichotomy – besides missing the point entirely regarding how people use social media in a way that acknowledges different contexts, audiences and identities – is precisely what lies behind the kind of victim-blaming that I have been studying for my thesis. Because if you think of privacy in terms of an on/off switch, then what is to stop someone sharing another’s data – after all, if it’s been shared at all, it might as well have been shared everywhere. So despite the good intentions of this website, the sentiment it expresses here is exactly the same as we see regarding victims of involuntary pornography. Don’t share unless you “want the world to know”. Therefore instead of helping to guard readers against privacy transgressions, this simplistic approach is cementing the right to commit such acts of aggression, by presenting it as to be expected.

Aside from this heavily problematic sentiment, the rest of the site is a bit of a puzzle, as it is laid out like some sort of video game that you scroll through and click on:

I can’t really think who this is designed for… Who learns about online banking like this?

And this “Threat Hunter” game… Who is this for?

The site also has a strange philosophy behind it, encapsulated in the warning “you wouldn’t do it on the street, why do it online?” (on the red bus below).

Like the warning not to share unless you “want the world to know”, the sentiment seems to present itself as common-sense, but again this misrepresents what people do with social media and computing. After all, there are plenty of things I do online that I wouldn’t do in the street, such as playing games, displaying photos and offering opinions to no-one in particular, such as here.

What this site tells us is that online security advice is still lagging a long way behind where it needs to be, if it is actually to be effective, and if it is to avoid making the problem worse rather than better.

Celebrity Explotation and the Selfie

Kirsten Dunst appears in a recent short film entitled Aspirational:

The film has been reported as being “about selfies”. Vanity Fair even suggests it is “anti-selfie”. And indeed it features selfies, but again they are used as a technique for expressing something else; something – surprise surprise – negative about young women.

Two young women notice Dunst standing by the side of the road and stop their car to take photos with her:

But despite the story ostensibly revolving around photography, and tangentially social media, it is in fact about rudeness and entitlement. For the women who run up to Dunst and take selfies with her neither ask her permission nor say thank you afterwards. There is no conversation, only the act of taking photographs. The process is made more excruciating by virtue of the young women’s posing, their moody faces in contrast to Dunst’s smile:

Dunst asks the girls “do you want to talk about anything?” The response is just blank stares and a request for Dunst to tag them, which she mutely refuses to do. An encounter of any kind that is based to this degree on one party’s gratification rather than mutual interaction is of course problematic. But why is the selfie being used to express this? I would argue that it’s because the selfie is culturally understood to be something, and to be somebody – to be the quintessential example of a problem that has long preceded it. After all, autograph hunters presumably have always been a problem for celebrities, with the added dimension that the desired signature could also have a cash value. The predatory, even hostile, stares they give Dunst are therefore not typical of selfies, but of the relationship between celebrities and the public more generally.

At one point Dunst asks whether one girl taking a selfie wants her friend to take the photo for her – the young woman replies “I don’t trust her”. The selfie is therefore not just representative of selfishness and poor social skills, it also implies inter-personal relationships that are lacking. Presumably they’re not very close because … they take selfies?

A glance of one girl’s phone shows the screen to be cracked: a little touch that reinforces our perception of them as problematic and irresponsible users of technology:

The girls drive off, enjoying the likes and “random followers” which this encounters has already brought them, blithely unaware of just how awkward and exploitative this social interaction was. And we as viewers are again instructed in what not to be, and how that is specifically expressed through an attitude that maligns and rejects selfies and those who take them.

Photographs and Threats: Emma Watson and the Allure of the Non-Consensual

The recent threats against actress Emma Watson demonstrate several interesting things about photography and the humiliation of women:

1. This case make absolutely explicit how intimate images (even the idea of intimate images) are used as a weapon to control and silence women. At no point did the media coverage question why anyone would respond to Watson’s address to the UN with a threat to reveal photographs. Why? Because the connection between “woman gives feminist speech” (or in fact, woman does anything at all) and “people threaten her with images” has become absorbed and normalised by a society that implicitly blames women for whatever happens to them.

Despite the widespread outrage at this threat, and at the earlier celebrity photo leaks, a study of the comments beneath the line on social media demonstrates that there is still a strong tendency in popular discourse to just shrug, and say that she should have expected it. And you can be certain that had photographs emerged, we would have again seen numerous voices chiding her for taking such pictures in the first place.

As I have observed extensively in my research, this knee-jerk response is voiced by good and rational people as well as misogynistic trolls, demonstrating that explaining away the abuse of women, or denying it through making it seem rational and normal, is something that people feel a very strong need to do. Presumably, otherwise one would find it simply too difficult to function within society. This brings to mind Sherry Turkle’s description of people’s attitudes to privacy violations online, in which “people simply behave as though it were not happening” (2011: 261).

2. As Valenti points out, despite the story turning out to be a hoax, it nevertheless reinforces a connection between outspoken women and humiliation. The use of the countdown clock and the website name “emmayouarenext” seem drawn from either the playground or a spy novel. But this use of a prolonged and unspecified threat nevertheless demonstrate the effectiveness of psychological forms of harassment, in which the mere prospect of something happening is enough to alarm and coerce. The countdown clock here performs a similar role to the warden in the Panopticon – he might be there, he might be watching, punishment might be about to happen, therefore the conditioned response is to assume that this is the case. Although none of Watson’s images were leaked in the end, it would be ludicrous to assume that she has not been affected by these threats. The effect of her wonderful speech has been overshadowed by the spectre of her humiliation.

3. The (unreliable) figure of 48 million page views of the site Emmayouarenext.com speaks for itself. It might be inflated, but its also believable that this website received huge volumes of traffic. The media’s eagerness to report on the story, even with very limited amounts of information, is both depressing and unsurprising – the humuliaition of women is news and entertainment at the same time. As with the earlier celebrity photo leaks, there are large audiences for these types of private images. Audiences that are actively seeking out photographs that have caused their subjects pain and humiliation. Audiences who understand the value and the thrill of obtaining non-consensual materials, in comparison with conventional forms of pornography. And it’s the audiences that really make this story possible: if there wasn’t this enormous hunger to access people’s private lives, then photographs of women could not be used in this way. If women’s nude photography wasn’t a source of shame, outrage and most of all prurient fascination, then they couldn’t be punished for, or with, such images. If this process of humiliation and punishment is ever going to be addressed, it needs to start with the audience, which is why the prevalence of articles calling on people not to look at private images was particularly heartening.

Lastly, it seems that photography, for women especially, is a dangerous business. The only way to protect oneself from this kind of threat is not to take pictures, and add this precaution to the enormous list already given to women: don’t go out alone / wear a short skirt / get drunk etc etc. But what I find particularly sad about this, is that the proscription against photographing oneself – such a harmless piece of fun in itself – is just another way in which women are denied a full social presence. Because what these threats and leaks and warnings to women suggest is that as society, we believe that being kept hidden – off the streets, away from the camera and certainly away from the UN – is apparently the only way to stay safe.

Dogs and Babies: The Happy Fantasies of Photography

I’m currently writing up my PhD thesis, and am working on a chapter on involuntary pornography. As you can imagine, this is not exactly the most cheery of topics, so this week’s blog post is going to try to be a bit lighter than normal to balance things out.

There’s an advert on UK television at the moment for the Halifax bank, which features a female photographer taking a series of heart-warming shots of dogs, families and babies.

These scenes of her hard work are presumably used to connote the bank’s commitment to its customers. As someone who worked as a photographer, shooting portraits and weddings and the like, I can assure you that the work is hard. I often went home exhausted, covered in grime and with a thousand-yard stare. But lots of people work hard – so why choose a photographer for this advert?

I think the answer lies in the public perception of photography – as tricky, maybe, involving a lot of vague notions of ‘creativity’ and technical expertise – but ultimately as something we could imagine ourselves doing. It’s interesting, but not threatening. That’s why mannequins in shops hold cameras and not microscopes.

Despite the hipster fetishization of film cameras in shops such as Urban Outfitters above, the photography industry has been radically transformed over the last 15 years, with the role of photographer being seen as less of a profession than a demarcation given to someone who is using a camera. But so too has the role of photography itself radically altered, with images incorporated into everyday life and communication in ways difficult to imagine a generation ago. Which is why I think this advert presents an interesting time capsule of what we want photography to be, despite the ever-increasing gap between the warm-and-fuzzy photographer, and the darker figures observable online of the creepshot photographer and revenge porn user.

In this advert, we are reassured about photography on a number of levels. It is friendly and funny:

It is patient and gentle:

It is well-prepared and determined to make others look good (although who needs that many lenses to take an indoor portrait of a dog?):

And it is reassuringly old-school, as conveyed by a medium-format camera on an unnecessarily-huge tripod:

Two things struck me about all this. Firstly, this list of qualities of the ideal photographer seemed to emulate many of the traditional attributes of femininity, in terms of being welcoming, empathetic, self-sacrificing, and considerate of others. The woman photographer is therefore reassuring to customers because she is the quintessential figure of feminine warmth (with the exception perhaps of the nurse or teacher). Secondly, the artifice of this construction is obvious not just in terms of its cultural wish-fulfilment, but also in the straightforward way in which it is enacted. As I watched the advert, I wondered why she had studio flash lights but no flash cable or wireless flash trigger on her camera (pedant alert!). Maybe she was just using the modelling lights to take pictures (odd), but in this behind-the-scenes shot, we can see the flash light being simulated off-camera:

Now, I’m not going to say “it’s an advert and its presentation of life is not realistic, what a shock!” – but rather point out that this provides a handy metaphor for the fabricated nature of cultural assumptions about photography more generally. The view the Halifax advert presents of photography – as a lark, and as a site for developing empathy with others – is very different from the uses I see photography being put to in my own research. There, photography is used as a way of punishing, shaming, and bulling other people, in order to maintain a state of inequality between ‘us’ (those who ‘do it properly’, whether in the form of the photos they take or in terms of identity more generally) and ‘them’ (those who ‘do it wrong’, and who take selfies, or do duckfaces etc).

I don’t want to undermine the more gentle aspects of photography – far from it – but I want to expand the definition, to encompass the bad as well as the good. Because the warm and fuzzy perception of photography maintained by examples such as this advert is ultimately quite damaging, in that it presents images and the people who take or use them as harmless, when they are often, unfortunately, anything but. For society to only think of photography in terms of babies and dogs is to further marginalise the people who suffer as a result of what is said about or done with photographs. Although I have loved photography since I was a child, I am certain that it is important to confront and understand the nature and extent of the darker side to the practice, as much as we might prefer the friendly fantasy that is presented here.