I watched a Channel 4 programme on Monday called Shut Your Facebook. As I was watching it, I couldn’t sit still for my excitement – here was social media discipline at its absolute zenith. The programme looks at the social media habits of young people, considering how each could be problematic in terms of getting a job, damaging the person’s reputation and so on. But it is really nothing more than an excuse to have a good long gawp at the behaviour of young people, and to tut tut at their drinking, their sexual innuendos and their apparent lack of control. And the show’s main message, a lesson solemnly and repeatedly imparted, relates to the importance of control, particularly self-control. Subjects are instructed in how to main a disciplined approach to one’s online persona, rather than ‘let it all hang out’. Thereby, a sublimated rage at young people’s freedom, and a disgust with their bodies and behaviours, is funnelled into a form of benevolent guidance. It’s very similar to other makeover shows, particularly What Not to Wear, in the way that it presents the correction of problematic subjects as a form of entertainment. For a wonderful analysis of What Not to Wear, considering the makeover show as a legitimation of gendered class disdain, I recommend Angela McRobbie’s book The Aftermath of Feminism.

The programme looks at the social media habits of young people, considering how each could be problematic in terms of getting a job, damaging the person’s reputation and so on. But it is really nothing more than an excuse to have a good long gawp at the behaviour of young people, and to tut tut at their drinking, their sexual innuendos and their apparent lack of control. And the show’s main message, a lesson solemnly and repeatedly imparted, relates to the importance of control, particularly self-control. Subjects are instructed in how to main a disciplined approach to one’s online persona, rather than ‘let it all hang out’. Thereby, a sublimated rage at young people’s freedom, and a disgust with their bodies and behaviours, is funnelled into a form of benevolent guidance. It’s very similar to other makeover shows, particularly What Not to Wear, in the way that it presents the correction of problematic subjects as a form of entertainment. For a wonderful analysis of What Not to Wear, considering the makeover show as a legitimation of gendered class disdain, I recommend Angela McRobbie’s book The Aftermath of Feminism.

Ok, so back to our undisciplined Facebookers. To truly capture what the show is doing, I’ll describe its main scenes:

The show starts with a montage of some images and video clips, featuring young people passed out, vomiting, bearing their bodies, sitting on the toilet and so on. The voiceover states that:

“we want to find the nation’s worst social media sinners, from online obsessives, to extreme oversharers, from the positively hopeless, to the startlingly stupid. We’re going to show them how their online antics can affect their real life prospects, and see if we can shock, shame or surprise them into thinking again.”

As a statement of intent, this does two things – it describes the techniques it will be using (e.g. shame) and positions the recipients as meriting this intervention, this punishment.

First up is “party-boy Christian”. We see a sequence of shots from his Facebook page, featuring drinking, nudity, blow-up penises and so on. He states that he’s not bothered about being private, or about other people’s perception of him in relation to these images. The voice over tells us that in real life (a statement in itself) Christian is a recruitment consultant, and sets up a bizarre sequence in which Christian sits in a couple of mock interviews. His manner is professional, and he reveals he is good at his job and exceeds the targets set for him. He states that “as long as you’re professional outside of work, what goes on outside of work doesn’t matter” – and who wouldn’t agree that we all have the right to a private life? Well, this show apparently, as it supports the invasion of privacy that is employers looking at online profiles (cue scenes of shock and disgust, and yet another excuse to look at naked bodies). Sure, Christian might be wise to make his profile private, but the shaming he is subjected to by one mock-interviewer left me stunned. “Repulsive… he’s a no-hoper…sic. End of the day, it’s shit… This is terrible, this is really bad”

The interviewer, above reprimands him saying “that’s not professional Christian, that’s not going to get you a job” – as McRobbie and Foucault argue, contemporary discourses of the self encourage a self-monitoring and regulation which makes the subject fit for work, productive, and able to engage with the demands of global capitalism. Christian’s partying ways clearly prevent him from being able to fulfil this objective, so he must be corrected. Although the message is being delivered in relation to his images, it is clear that he is being shamed for the behaviour itself. The interview concludes with a warning: “carry on doing what you’re doing in your own sweet way, but you won’t go anywhere.” The message is clear: do as we say, or you don’t get the life you want.

Next up is Charlie, a young woman who, again, loves to party with her friends. Cue montage. The problem, we hear, is that her friends like to tag photos of her which she finds ugly or embarrassing. Cue more photos. We are encouraged to see that yes, Charlie does seem to do a lot of embarrassing things, from pulling funny faces, to passing out on the floor. Not entirely unusual for a woman her age. But here such behaviour is presented as problematic, and in need of correction. But rather than ask her friends not to tag her, cue the arrival of a photographer who will take some more flattering snaps of Charlie for her profile.

“Being camera-ready is clearly a concept Charlie has yet to master” we are told. The photographer will “give her, and you, tips for taking a profile pic to be proud of” – contrasts of pride and shame further the programme’s claimed objective to regulate viewers, as well as the subjects depicted. Also, rather than address anti-social group behaviours (her friends after all know that this tagging distresses her), the message is that she should change herself, and make her profile less embarrassing by being less embarrassing. In essence, she should be the photo she wants to display to the world. “By me telling you to turn away” says the photographer “you’re losing three inches” – the fact that this is ludicrous for someone Charlie’s size is lost beneath a wink shared with the viewer, in which we all want to look smaller, don’t we, eh?

To impart these messages, the programme also sends “fellow photo disaster area” Chelsea Healey to speak to Charlie. This exchange reminds me of a page on the defunct revenge porn website Pink Meth, where victims were encouraged to submit stories of their comeuppance as a warning to other women to “lock down their dirty pics”. In both cases, we have those who have been punished according to society’s rules of photography, imparting the need to be regulated to others. A perfect circle of discipline. Chelsea asks Charlie how she feels in relation to her new photos – “more classy” is the answer. The class-dimensions of this narrative, and the taming of her wild, sexual persona online, are another thesis in themselves… “She now looks more hot stuff, than hot mess” the narrator concludes.

There follows a bizarre section featuring a ‘Naked Nerd’ – a naked man whose role it seems is to impart advice and coerce viewers into agreeing with the show’s edicts, whilst giving the camera something to focus in on. “You can trust him, because he’s naked” we’re told. The connection between any form of ‘oversharing’ and physical nudity is one that’s been made before, such as by Ben Agger. But here it serves merely to up the flesh content of the show, and provide and interestingly hypocritical contrast between good public bodily display (when used by a TV company to prove a point) and bad public bodily display (when done by young people).

The next subject is Brayden, whose social media use conflicts with his boyfriend’s wish to have a conversation. Cue a scene where he is shown to be a “dick @ dinner”, by virtue of texting and snapping throughout a meal at a restaurant.

Now, there is a big difference, in my mind, between the subjects discussed so far in this programme. Whereas Charlie or Christian’s behaviour is labelled as “sick” or “embarrassing” and in need of correction, Brayden’s use of his phone causes a different problem, in that it distresses his partner, and makes him feel ignored. It’s Brayden’s lack of consideration for his boyfriend’s needs that’s the problem, not his social media use per se. The programme continues by asking if we, the viewers, are “phubbers” – i.e. phone snubbers, people who focus on their phones instead of those around them. We are then asked to report the worst “phubbers” by tweeting to the programme, via #shutyourfacebook.

Interaction with the programme is doubly disciplinary: either in the form of following a link to read their advice, or through reporting their friends’ transgressions. Peer regulation, through tweeting, is therefore naturalised as a fun accompaniment to watching television.

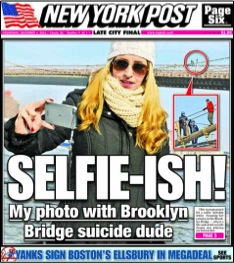

The next section addresses a problematic selfie-taker, in the form of Dominique, whose sexy selfies, we are told, despite being liked by scores of men, “haven’t helped her find a man in the real world”. The voiceover wonders whether it’s because Dominique in person looks different from her photographic self (mostly because she’s wearing more clothing). There follows a strange conversation between her and Chelsey Healey, in which Chelsea questions what Dominique enjoys doing, and marvels at the answer: extreme sports. Chelsea says “I’d never have guessed”, implying that Dominique’s “sexy” online persona should be read as encompassing the totality of her interests. This ties in with a troubling feature of discourse regarding online identity performance, namely that we should strive to present one ‘authentic’ self. Mark Zuckerberg is a central proponent of this, repeatedly stating that “you have one identity”. Here we see the limitations of this norm, in that identity is never singular, but must be understood as shifting, multiple and unstable. Dominique is a perfect example of this – she enjoys sports and sexualised self-performance, but the coercion towards embodying one coherent self might lead her to favour presenting one aspect of her life over others. Which then, paradoxically, means that people like Chelsea get puzzled when they hear she is actually a more complex person that her pictures imply. The problem is not the pictures – it’s how we interpret them. Assuming that we can know anyone from their pictures, no matter what they look like, is a fallacy.

But the programme persists, and displays Dominique’s images on a wall for the judgement of “the local lads”. One set of images displays her sexy side, one her interest in sports. The interpretations the male critics make of the images is predictably vapid, in that the ‘sexy’ set is “not as natural” and “off-putting”. The fact that they are asked to choose which “girl” depicted they would want for their girlfriend makes a mockery of the whole ‘experiment’, in that they condemn Dominique’s sexy pictures for looking too focused on finding a man, whilst firmly reinforcing the sense in which selecting and presenting these images should be with a male viewer in mind. Presumably Dominique will find such advice more compelling when it’s offered by a male? The voiceover concludes that “Blokes in real life want a girl who covers up online”. Generalisation, tick; slut-shaming, tick; hypocrisy; tick. And the programme cannot resist one last swipe at Dominique, for not following their advice. We are told she continues to upload sexy photos, and concludes that “who needs one boyfriend when you can have thousands of strangers giving you the thumbs up?” Her refusal to play ball and ‘tone down’ thereby places her in a devalued position, where intimacy is foregone in favour of the empty esteem of strangers. That the show delivers such a blatant moral condemnation almost as an afterthought demonstrates the prevailing sense of disgust which motivated its creation. The point is hammered home by the Naked Nerd, who advises with some statistics produced as if from thin air, that men like girls who keep their clothes on. And to unpack that statement would require yet another thesis.

The last subject is Caolan, a young man who has become popular on Facebook through producing short videos of himself and his friends acting out dramatic storylines set within a series of hotels and bars. It looks like a young person’s version of Dynasty, so no wonder people watch it. He speaks quite frankly about wanting fame and luxury, is depicted drinking champagne, and reveals that he uses credit cards and loans to fund his tastes. He’s fairly dismissive about his debt, and indeed nothing seems particularly abnormal about his behaviour – young people enjoying life, spending too much money, looking for approval and notoriety. But again this must be turned into a morality tale, and Caolan is given two large bags of pound coins to carry around, a symbolic version of his debt. Caolan expresses dismay at his debt seeming “more real”, his punishment apparently working.

The last subject is Caolan, a young man who has become popular on Facebook through producing short videos of himself and his friends acting out dramatic storylines set within a series of hotels and bars. It looks like a young person’s version of Dynasty, so no wonder people watch it. He speaks quite frankly about wanting fame and luxury, is depicted drinking champagne, and reveals that he uses credit cards and loans to fund his tastes. He’s fairly dismissive about his debt, and indeed nothing seems particularly abnormal about his behaviour – young people enjoying life, spending too much money, looking for approval and notoriety. But again this must be turned into a morality tale, and Caolan is given two large bags of pound coins to carry around, a symbolic version of his debt. Caolan expresses dismay at his debt seeming “more real”, his punishment apparently working.

But again, the voiceover reveals that he went back to his old spending ways. The concluding comment delivered to Caolan, however, is notable for its comparable lack of venom. None of the moral disgust levelled at Dominique, but instead a shake of the head and tsk in the form of “he calls himself a student”. Discipline in relation to online behaviour is therefore highly gendered, and not distributed equally. Economic transgressions are presented as being not as problematic as sexual impropriety.

I feel I should submit this programme instead of my thesis, and just point at it.